Timeline

476

The Roman Empire witnesses a sharp decline, as Barbarian tribes infiltrate and plunder key Roman Cities. This triggers an economic collapse, prompting the more affluent populace to migrate to rural areas. During this tumultuous period, the Catholic Church emerges as a crucial aid, assisting urban populations grappling with the loss of infrastructure. Artisans, facing city perils, are compelled to shutter businesses and seek refuge in the safer countryside.

900

In a significant move, three Benedictine monks depart from Rome and establish the "San Salvatore" abbey within the Castelli territory. This abbey evolves into a robust community that actively supports local residents through diverse endeavours such as agriculture, shepherding, artistic crafts like painting and ceramics, infrastructure development including roads and water systems, education, and providing aid to the underprivileged with sustenance and shelter. Over time, the abbey gains prominence as a pivotal focal point for neighbouring villages, assuming administrative authority over the region. Simultaneously, the inhabitants of the Castelli Valley embark on constructing fortified castles to safeguard themselves from the perils posed by travellers and pirates traversing their lands. This strategic action is the origin of the name "Castelli," reflecting its connection to these protective structures.

1000

As the Abruzzo region, including Castelli, faced challenges from Turkish pirates and foreign groups seeking access to Italy's eastern coast, the abbey became a focal point for the formation of villages and castles, fostering mutual support and knowledge exchange among the communities. Meanwhile, within Castelli itself, the local residents harnessed the region's resources—clay soil, torrents, and endless forests—to delve into ceramics production. This initiative not only resulted in making practical ceramic pieces for daily use, but also involved exploring and innovating to create vibrant colours by using plant essences and stones.

1400—1499

The colour blue has an intriguing history. It is notably absent from the Bible and 20,000-year-old European cave paintings, not even having words to describe it in ancient texts. The first blue pigment emerged around 2200 B.C., courtesy of the ancient Egyptians. However, it took nearly 3,000 years to create a stable pigment suitable for various surfaces. This ultramarine blue, aptly named for its origin "beyond the sea”, reached Europe through Italian traders in the 14th and 15th centuries. Its price was so exorbitant that it equaled that of gold, making it a rare treasure reserved for royalty and esteemed artists like Michelangelo, especially for their church commissions. Initially, this vivid blue graced the robes of Madonna. Meanwhile, in the 15th century, Castelli ceramists developed their own striking blue hue, known as Castelli blue. It rivalled ultramarine in brilliance and beauty. This unique blue began to adorn ceramic pieces commissioned by nobility and royalty, swiftly becoming the new standard for ceramists.

1400—1599

The beginning of renaissance in Italy. It marked a profound shift in art, literature, science, philosophy, and politics. During this era, the monks of the abbey were immersed in diverse activities such as agriculture, sheep farming, and working with clay. As villages began to take shape around the abbey's influence, a vibrant exchange of both knowledge and goods took root. Notably, the expertise in clay work gradually expanded beyond the abbey's confines, evolving into a valued trade commodity that would eventually become a hallmark of the region.

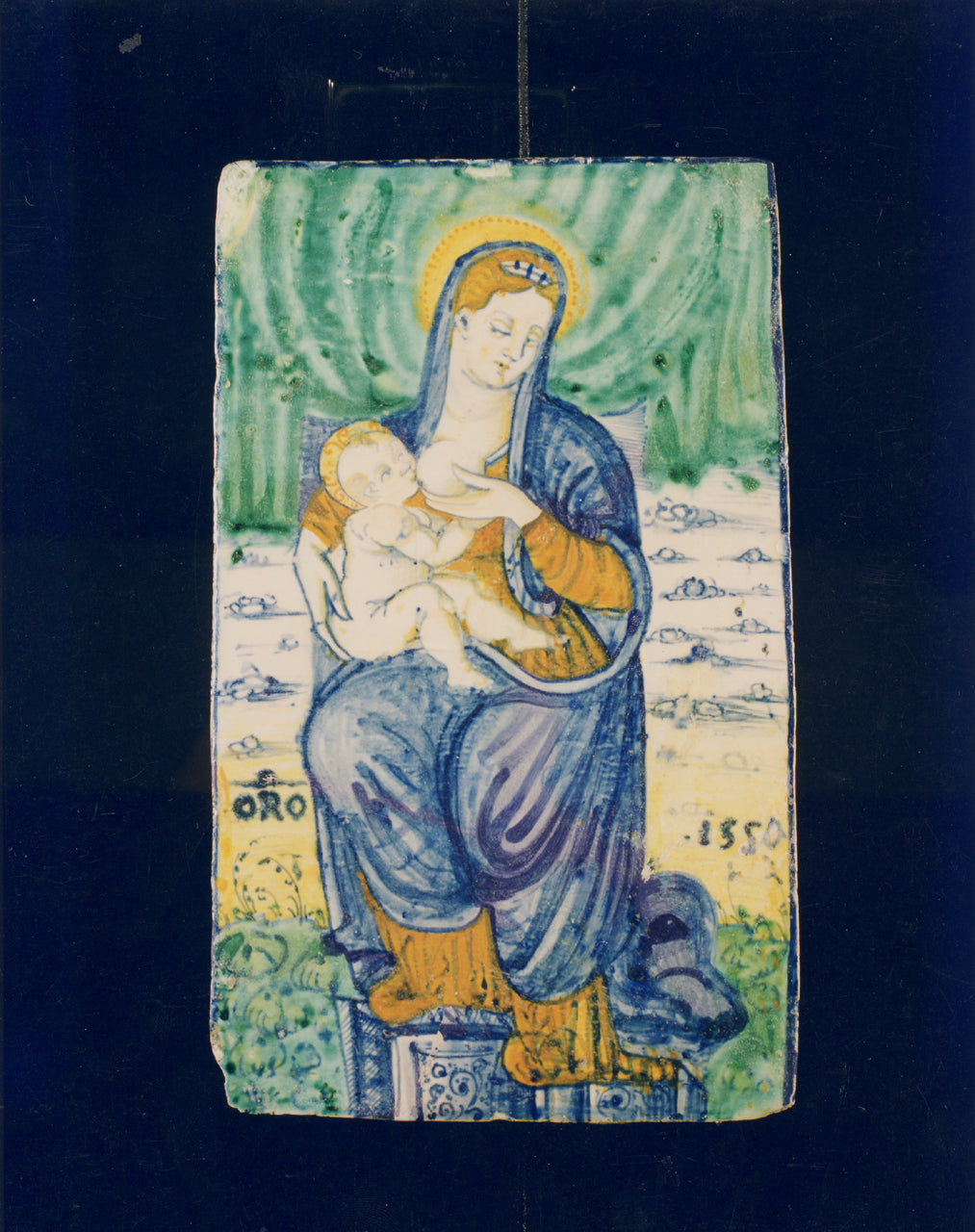

1551

A pivotal moment in Castelli ceramics arrives with Orazio Pompei, a groundbreaking ceramist, who elevates the craft to an art form by embellishing tiles with intricate paintings. His portrayal of Madonna nursing her baby becomes a milestone in Castelli's ceramic history, as it departs from practical tableware. This innovation sparks a wave of creativity, expanding into artistic pieces, decorative wall panels, and vases that swiftly capture the admiration of nobility and society at large.

1540—1555

During this period, Orazio Pompei creates his internationally renowned apothecary jars and drug pots, which now grace the halls of prestigious museums such as The Met, The Louvre, and The British Museum.

Approximately 1560

Orazio Pompei leaves a permanent mark by adorning 500 tiles for the “first” ceiling of a quaint rural church, now known as Chiesa San Donato. This church has become known as “The Sistine Chapel” of Maiolica, paying homage to Pompei's transformative contribution.

1615—1617

Following the renovation of the San Donato church, a collective of Castelli's most prominent ceramist families undertakes a remarkable endeavor, adorning the church's “second” ceiling with a thousand meticulously painted tiles.

Timeline

1615—1617

Carl Antonio Grue, a luminary from the Grue family workshops that have thrived since 1630, pioneers a "luxury line" of majolica. This collection stands out for its innovative shapes, intricate decorative patterns, and a fresh historiated style. Revered for its rarity and opulence, Grue's majolica gains the distinction of being regarded by collectors as Italy's most exquisite.

1630—1800

Across these centuries, successive generations of the Gentili family have indelibly shaped the realm of ceramic art, a legacy now showcased in museums worldwide. Through their creative hands, plates and cups transformed into canvases bearing the weight of significant historical narratives from their era, leaving a remarkable and enduring historical imprint.

Until 1750

Castelli ceramics undergoes a transformative journey marked by the refinement of distinctive colouring techniques and enhanced production methods. As these creations garner acclaim, their allure extends to European nobility and even royal residences. Today, the legacy of Castelli ceramics is celebrated across the globe, with pieces gracing prestigious museums like The Met, the British Museum, Louvre, and the Hermitage.

1906

A pivotal year as Beniamino Olivieri and Felice Barnabei establish the School of Castelli Ceramics, breathing new life into the local ceramic tradition. This institution evolves into the State Art Institute for Ceramics, and subsequently, the “Liceo Artistico per il Design”, shaping the artistic trajectory of the region.

1954

With the goal of interpreting the two ancient ceilings of Castelli, created in the 16th and 17th centuries for the small church of San Donato, the Castelli Art Institute was commissioned to create a new third ceiling. This involved decorating 356 panels, which were subsequently exhibited at the Triennale di Milano. Following several exhibitions in different locations, the remaining 258 panels have all returned to Castelli and are now on display at the Castelli Art School.

1965—1975

The monumental nativity scene. Created by the Castelli Art Institute, this Nativity scene features 54 statues depicting the birth of Jesus. Over the decade, it evolved to reflect contemporary events, including the moon landing, the Second Vatican Council, and the abolition of the death penalty. It was exhibited in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Tel Aviv in 1970 and in St. Peter's Square in Rome in 2020.

1986

A defining year as the beginning of the International Collection of Contemporary Ceramic Art takes place, serving as a comprehensive repository for global ceramic exploration. This remarkable collection showcases the creations of more than three hundred modern artists hailing from fifty nations, cementing its status as a paramount reference for ceramic artisans around the world.

Present

Castelli ceramics persists as a fusion of tradition, innovation, and artistic ingenuity. The Art Institute “Liceo Artistico per il Design” remains a steadfast beacon, nurturing and empowering ceramic artists by seamlessly connecting historical roots with future possibilities. Árgillarte is founded to bring Castelli's art pieces and its rich history to a global audience.